- The planet named Epsilon Indi Ab is the first directly imaged mature exoplanet close to the Earth and is classified as super-Jupiter, said a press release.

In a major discovery, IIT Kanpur Professor Dr Prashant Pathak along with a team of international astronomers have traced a giant planet, similar to the size of the sun, orbiting in the solar system.

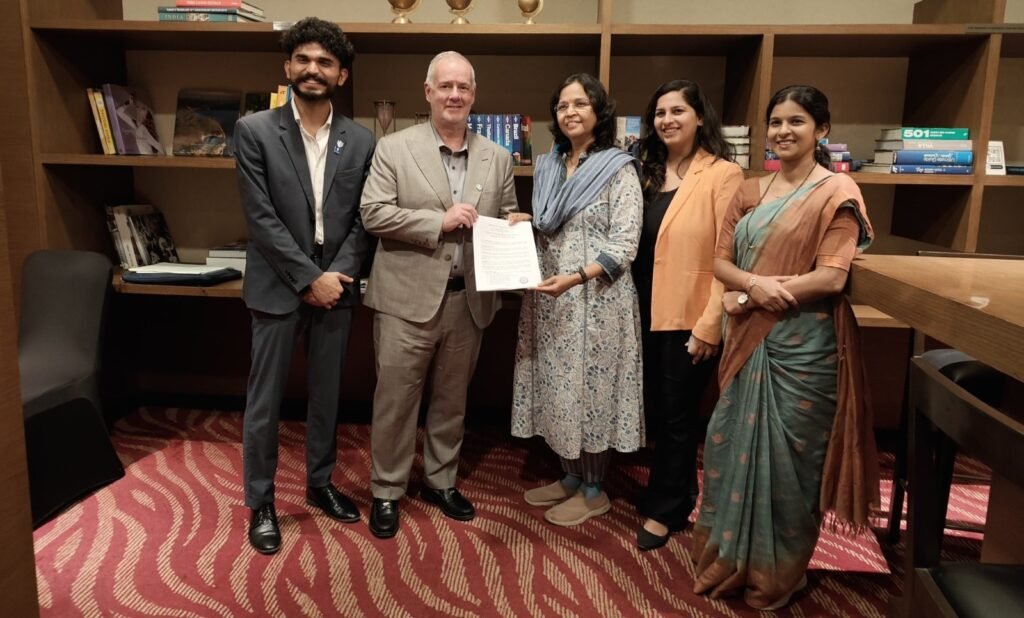

As per a press release, Dr Pathak from IIT Kanpur’s Department of Space, Planetary & Astronomical Sciences, and Engineering (SPASE), who is also a part of the international team of astronomers, discovered the planet through Direct Imaging techniques using the James Webb Space Telescope’s (JWSTs) Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI).

The planet named Epsilon Indi Ab is the first directly imaged mature exoplanet close to the Earth and is classified as super-Jupiter, said the press release.

The planet has been classified as super Jupiter due to its mass, which exceeds that of Jupiter by at least six times, making it significantly larger than any planet in the solar system.

As per the finding, the newly discovered planet is located 12 light-years away from Earth, and is quite cold, with a temperature of about -1°C (30°F).

The finding further revealed that the planet’s orbit is also immense, circling its star at a distance 28 times greater than the distance between Earth and the Sun.

The planet’s atmosphere appears to have an unusual composition that indicates a high metal content and a different carbon-to-oxygen ratio than the other planets in the solar system planets.

It may be mentioned here that attempts that were made earlier to study the giant planet Eps Ind Ab using radial velocity measurements did not yield results as the planet’s orbital period is around 200 years and the data from short-term observations was not sufficient to accurately determine the planet’s properties, said the release.

More details of the discovery and the research behind it have been published in the world’s leading multidisciplinary science journal, Nature, stated that a press release.

Why direct imaging: Unlike indirect methods that infer a planet’s existence through its gravitational influence or the dimming of starlight as it passes in front of its host star, direct imaging allows astronomers to directly observe the exoplanet itself.

The team decided to follow a direct imaging approach since the overwhelming brightness of the host star would typically hinder detecting the exoplanet’s faint light.

JWST MIRI camera equipped with a coronagraph blocked the starlight, thereby creating an artificial eclipse.

The technique enabled the detection of faint signals around bright objects, similar to observing a solar corona during an eclipse.

Speaking on the discovery, Dr Prashant Pathak, who is a key member of the research team, pointed out that the discovery is exciting because it provides a chance to learn more about planets that are very different from the existing ones.

“The planet’s atmosphere appears to have an unusual composition that indicates a high metal content and a different carbon-to-oxygen ratio than we see on our own solar system planets. This opens up fascinating questions about its formation and evolution. By studying Eps Ind Ab and other nearby exoplanets, we hope to gain a deeper understanding of planetary formation, atmospheric composition, and the potential for life beyond our solar system,” he explained.

Prof Manindra Agrawal, Director of IIT Kanpur said that the discovery is a major milestone in exoplanet research and sets the stage for future discoveries.

“Being able to directly image a planet close to us provides an unprecedented opportunity for in-depth study. Dr Prashant Pathak’s work in collaboration with international experts highlights the global contributions of IIT Kanpur in advancing our understanding of space,” she added.

Elisabeth Matthews, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, and the lead author of the research article said “We were excited when we realized, we had imaged this new planet. To our surprise, the bright spot that appeared in our MIRI images did not match the position we were expecting for the planet.”

Thomas Henning, Emeritus Director at MPIA, co-PI of the MIRI instrument, and a co-author of the underlying article, highlighted that the team’s next goal is to obtain spectra that provide a detailed fingerprint of the planet’s climatology and chemical composition.

“In the long run, we hope to also observe other nearby planetary systems to hunt for cold gas giants that may have escaped detection. Such a survey would serve as the basis for a better understanding of how gas planets form and evolve,” he said.